Review by Simon Jenner, September 8 2025

★★★★

“A child is a silence between two explosions.” When a deaf child falls silent, shot dead in a town under occupation for not heeding a command, the whole town goes deaf. Falling silent becomes an act of defiance. The book-length poems of Ilya Kaminsky’s 2019 Deaf Republic are brought to the Royal Court Downstairs till September 13 in a distillation of 105 minutes. A collaboration with Sign Language poet Zoë McWhinney, it’s co-directed and co-written by Bush Moukarzel and Ben Kidd of Dublin’s Dead Centre.

Though Deaf Republic was itself written in the shadow of the 2014 invasion, and sensing a further one, this seems horribly prescient. Especially the weariness of resistance after two years, a mantra latterly repeated to despair. As a non-specific metaphor for creative resistance it still resonates, though echoes of more than one contemporary conflict lend urgency. Underscoring the implicit terror of disablism under occupation (voluntary or not) it offers few consolations. There’s a drone, there’s complicity.

Photo Credit: Johan Persson

At the start, Romel Belcher and Caoimhe Coburn Gray alternate, she for the hearing and Belcher by sign. They’re a warmly communicative couple (as Sonya and Alphonso, emphatically not their names they proclaim), yet their storyline is central. Discussing signing amidst a d/Deaf and hearing cast, ambiguities emerge as critiques: for instance the word “colonialism” has two different signings: for those occupying and taking, and from those from whom land and liberty is taken. Though there’s little time to develop that conversation, it stays. When Dylan Tonge-Jones’ hapless hearing character Pavel gradually acquires the language from Lisa Kelly’s Lisa, it’s an act amplifying resistance to such invasion.

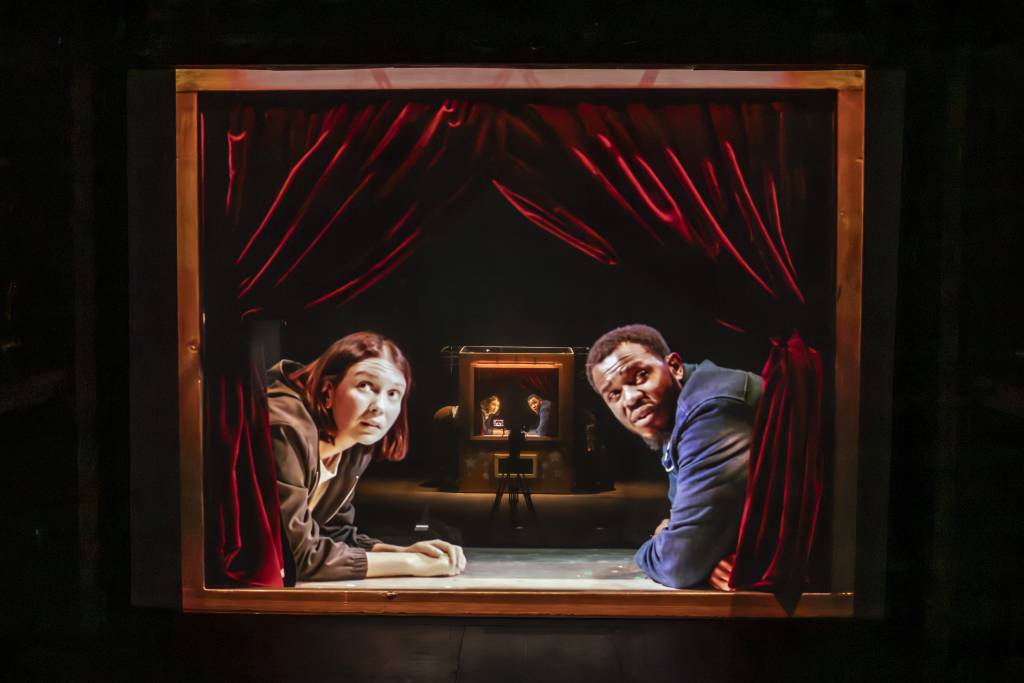

It’s almost cubist theatre: you’re assailed with analogous images from queasy perspectives: puppet versions of real actors (Mae Leahy’s costumes and Cillian O Donnachadha’s puppetry consulting to the fore), miniatures of toy jeeps switch for a real one. Sometimes gauzed over with a translucent curtain, at all times it’s mesmerising. Much of Kaminsky’s language punches through, and whilst signing Grant Gee’s remarkable use of video combines with its physical analogue in Jeremy Herbert’s set: a video’s giant close-up of a puppet-show intercuts with a physical miniature, where giant hands intrude. So where language falls, it falls hard, with intense visual metaphors: “Deafness is suspended above blue tin roofs…” It’s a world of delicate “noes” when only a rasping “yes” is acceptable.

An opening simplicity dissolves into guignol. Azusa Ono’s lighting terraces all this into a mix of magic-lantern show and hideous cabaret, notably later scenes sleazed in a nightclub with added death. Despite the hearing being told they’re not excluded there’s Kevin Gleeson’s sound and composition; which muffles and distorts so you almost zone out to watching bright sound from somewhere else.

Some will find the staging congested. Ritual repeats of puppeteering and resistance can blunt point and poignancy, but each is choreographed, each matched where applicable with surtitles and speech, often in hilarious collision. Elsewhere it seems a compelling balance of realpolitik, metaphor, states of being and storytelling. Indeed tenderness here is a thing of lightning-strokes,

And you follow storytelling with the irresistible language when it’s foregrounded. It’s shattered into shard-like twists with “crutches of bone” and an early stark simile. Litanic incantation alternates with sign language, a semaphore between two languages: “The body of the boy lies on the asphalt like a paperclip.” To underscore the puppeteer aesthetic, aerial consultants Chrissie Ardill and Kat Cooley expand the possible by crafting a vertical scale that turns the bijou puppet show into epic spectacle. So each time someone is killed, they’re winched up into the flies on ropes and pulleys like dead meat. Then elegantly dropped down.

Photo Credit: Johan Persson

Laced with dark humour, poetry often drives the action: “The deaf don’t believe in silence. Silence is the invention of the hearing”, which counters Eoin Gleeson’s invading commander on repeat: “this is an accessible war!” Just as he asserts this, the surtext monitor having repeated everything he says, lowers to the ground and dies. The very tech of the place is against him. Deaf Republic is full of such Jacobean dumb-shows, as in the late close-up of two women trying to dispose of Gleeson’s invading soldier.

That ruthless resistance, cracked by puppeteer Momma Galya (Derbhle Crotty as a mix of Joel Gray and La Passionara) to the two women who help her, Kate Finegan and Lisa Kelly, has a pacific counter. Even Galya warns: “Poems are no match for a man with a machine gun,” whilst urging on what seems to the two women “another soldier and another soldier.” It’s contradicted though, in the self-accusing: “We lived happily during the war. And when they bombed other people’s houses, we protested. but not enough.”

Deaf Republic though settles on the provisional with furious questions: “At the trial of God, we will ask: why did you allow all this? And the answer will be an echo: why did you allow all this?” The show’s (and poem’s) nature allows sketchy identification with Sonya and Alfonso above all. Nevertheless its claustrophobia overwhelms and moves, whilst leaving Dead Centre room for yet another slant on Kaminsky’s imaginary.

Photo Credit: Johan Persson